Heat Pumps Reducing your Building’s Reliance on Fossil Fuels

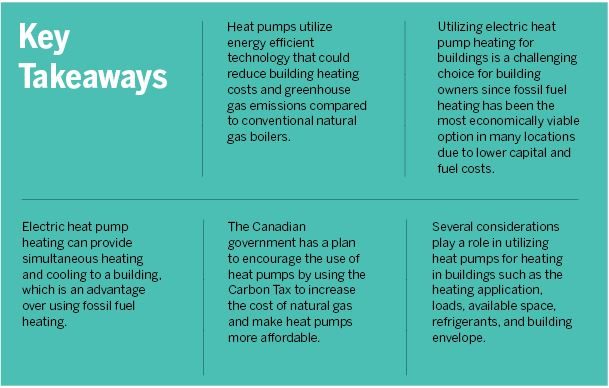

In Part 1 (https://hhangus.wpengine.com/heat-pumps-reducing-your-buildings-reliance-on-fossil-fuels/) of this series, we introduced the use of heat pumps for building heating and how they present an opportunity to mitigate the effects of climate change. In Part 2 (https://hhangus.wpengine.com/heat-pumps-reducing-your-buildings-reliance-on-fossil-fuels-part-two/) we discussed the cost implications to owners and operators, as well as considerations, opportunities and risks present for heat pump heating and how to navigate them. In this final installment, we review refrigerant options and additional considerations impacting a building owner or operator’s decision to implement heat pumps, along with a summary of key take-aways.

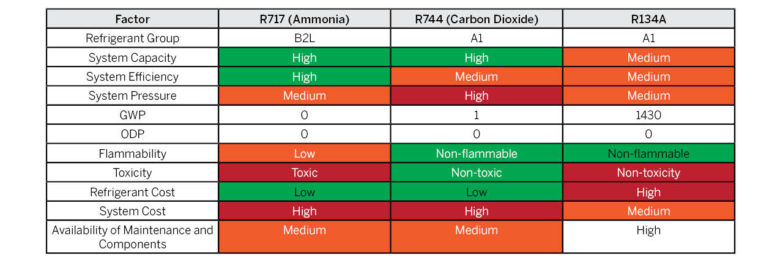

When it comes to selecting a heat pump, the refrigerant will play a role in determining the operating temperature of the heat pump. This is critical to older buildings that require high temperatures for heating due to poor thermal performance of the building envelopes. It is important to consider that synthetic refrigerants such as R134A and R1243Zde, which are commonly used in commercial heat pump applications, have some limitations on their maximum operating temperatures. In addition, some of them have higher Global Warming Potential (GWP) as well as higher refrigerant costs. See Table 1.

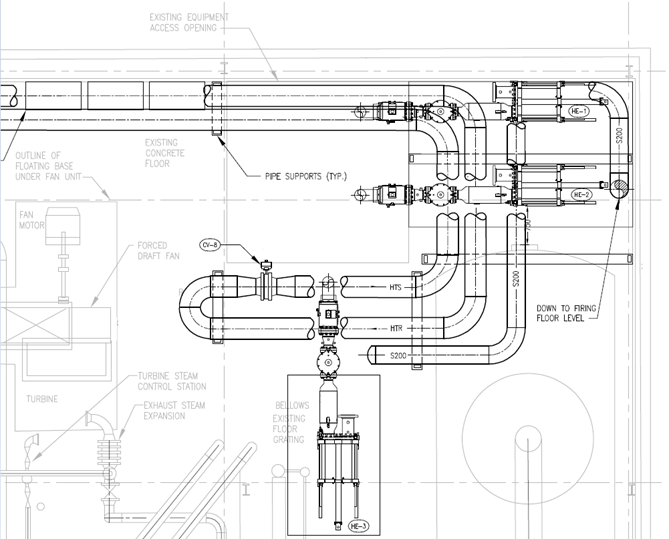

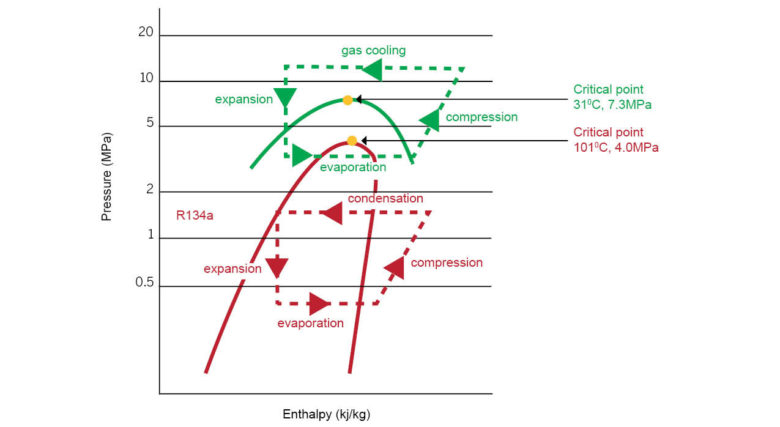

Natural refrigerants, such as Ammonia (R717) and CO2 (R744), can achieve higher operating temperatures and have minimal/no GWP in addition to relatively lower refrigerant costs. However, the capital cost for machines using Ammonia (R717) and CO2 (R744) is generally higher than that of synthetic refrigerants. This is because these refrigerants operate at much higher elevated pressures (up to 2000~3000 PSI for CO2). See Figure 7. Piston reciprocating and screw compressors can be used for these machines. This can sometimes result in additional noise suppression requirements for certain projects that use these types of compressors. Natural refrigerants are typically used for industrial application; however, they are making their way to small scale applications. It is worth noting in the case of using ammonia as a refrigerant that, based on the refrigerant charge, there may be additional challenges such as code requirements for room construction and emergency refrigerants leak detection and evacuation.

Commercial heat pumps can provide hot water for heating to a maximum temperature between approximately 60 and 70°C (140 to 160° F), while industrial heat pumps can operate at temperatures up to 95°C (203°F). These differences in temperature limitations would have some effect on the maximum COP that these types of heat pumps can achieve. Some system designs can combine two refrigeration cycles, each having separate and different refrigerants: one is synthetic while the other is natural, resulting in the best of both worlds of cost versus efficiency.

One final item to consider is the phase out schedules of refrigerants. While many of the commercial synthetic refrigerants currently on the market do not have set phase out dates, it is possible that such refrigerants would fall under regulatory scrutiny that may require them to be phased out or replaced in the next 10 to 15 years. Natural refrigerants do not face such risks.

Other Considerations

Whole-building Energy Modeling

There are several other considerations that play a role in utilizing heat pumps for building heating. One of their main operational advantages is that they can provide heating only, cooling only, or simultaneous heating and cooling. It is easy to quantify the energy costs for heating or cooling using a heat pump as a dollar value per unit of heating or cooling. However, as previously noted, it becomes harder to quantify the benefits of a heat pump in a simultaneous heating and cooling scenario. At the design stage, a data-driven energy model of the building systems can help owners evaluate the true benefit of using heat pumps, especially for simultaneous heating and cooling, and a wide variety of modeling tools is available to engineers in this field. These tools can use real building heating and cooling load data to quantify the savings and operational advantages that a heat pump can bring when providing buildings with both heating and cooling at the same time.

Building Envelope

While not typically considered in the same context, the thermal performance of the building envelope is an important system to analyze and study along with heat pump technologies. Certain heat pumps can have limitations regarding the maximum supply water temperature (SWT) they can achieve. At the same time, the thermal performance of the building envelope defines the need for higher or lower SWT. For instance, high performance building envelopes enable the use of lower temperature heating systems to maintain comfortable temperatures indoors, which expands the list of heat pump technology options that can be used. It is important to note that, as technology improves, heat pumps are able to operate at even lower ambient temperatures and to produce even higher supply water temperatures. Consequently, it is possible to find heat pump products for most climates and buildings. However, there are undeniable synergies between high performance envelopes and heat pumps to achieve overall high building energy and carbon performance and, as such, these two energy conservation measures should be bundled whenever possible.

Geoexchange Systems

Tying heat pump systems to geoexchange systems can help heat pumps provide heating to buildings during peak winter days with no performance deterioration when compared to air source heat pumps (ASHP). Geoexchange systems utilize the ground as an energy source during the winter and as a sink in the summer. When coupling such systems with a heat pump, the caveat is to be able to accurately balance the thermal energy of the system across the seasons to avoid depleting the thermal source in the ground. This concept can be analogous to using the ground as a thermal battery that operates seasonally. This thermal battery charges during the summer where the heat pump cools a building and rejects heat to the ground, and in the winter the thermal battery discharges by acting as a heat source that provides thermal energy to the heat pump. In general, Thermal Energy Storage (TES) systems apply to refrigeration systems including heat pumps and can help in peak load management for building thermal loads; taking this into consideration when implementing heat pumps can result in both operation and economic gains.

Domestic Hot Water

One final consideration is that heat pump systems can be utilized for domestic hot water heating applications. Such integration can be relatively easy to implement from a design standpoint and can often result in capital and operational cost savings on domestic hot water heating equipment.

Simultaneous Heating and Cooling

Heat pumps can provide heating and cooling at virtually any time of the year, which provides the ability to control space conditions independently from each other. This allows for some zones to be in cooling mode while other zones are in heating mode, leading to increased occupant control and comfort. This is particularly important during shoulder seasons where some zones might require cooling (e.g. south facing), while other might require heating (e.g. north facing). This is a benefit of heat pumps compared to systems like a conventional 2-pipe Fan Coil systems with a Chiller and Boiler plant, where a seasonal changeover must be performed, and limits all the fan coils in the system to be in either cooling or heating mode.

The Bottom Line

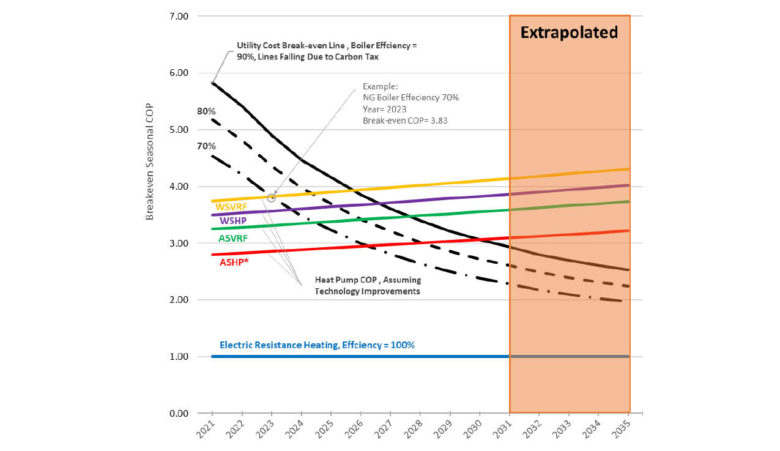

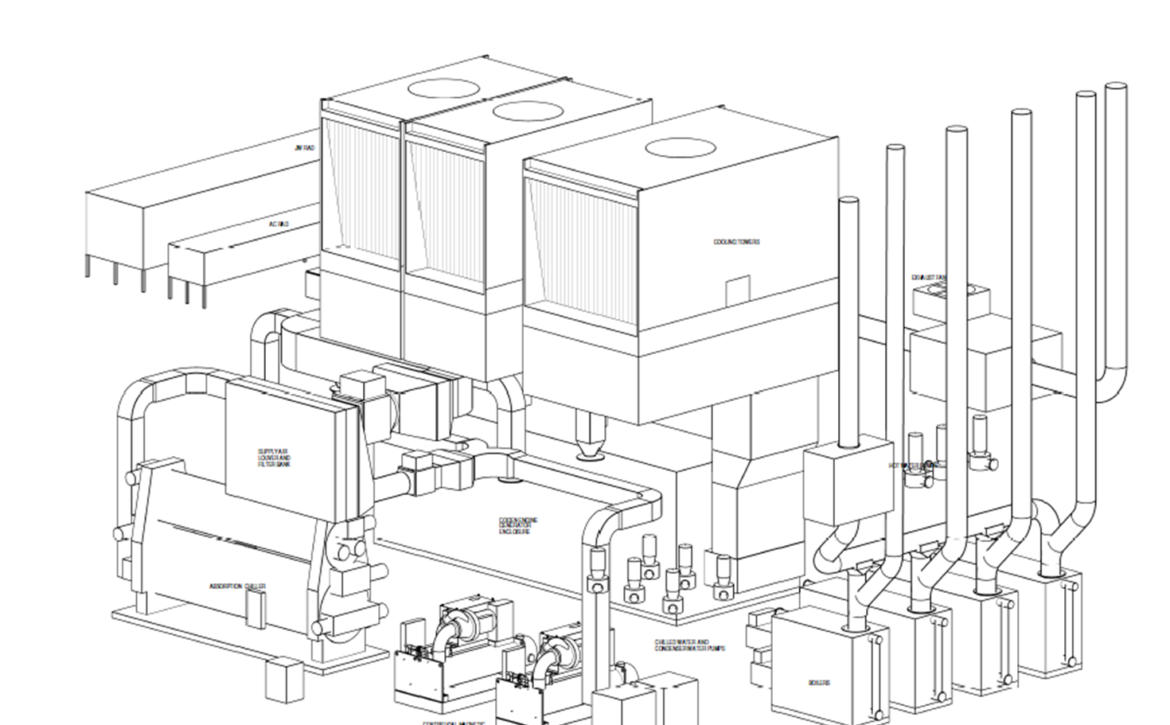

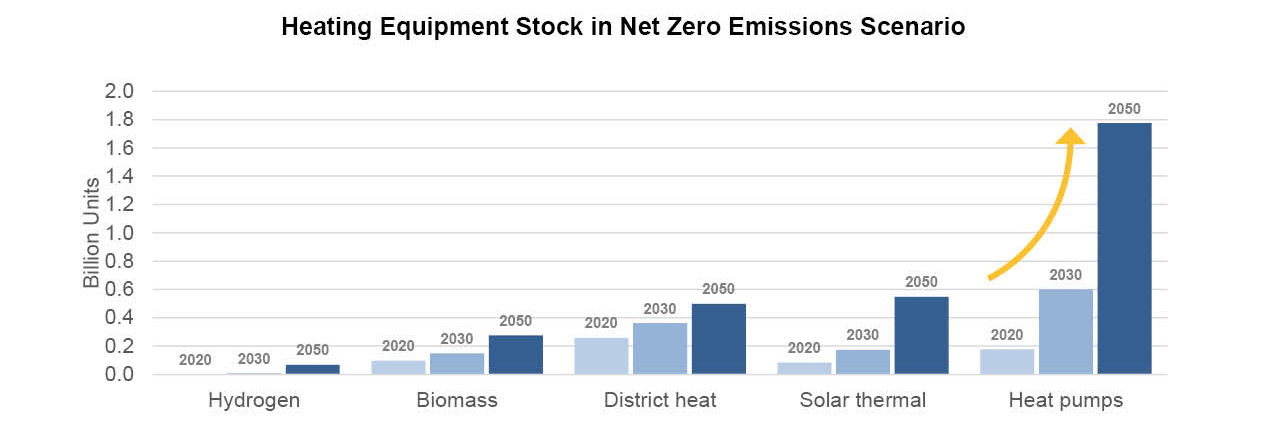

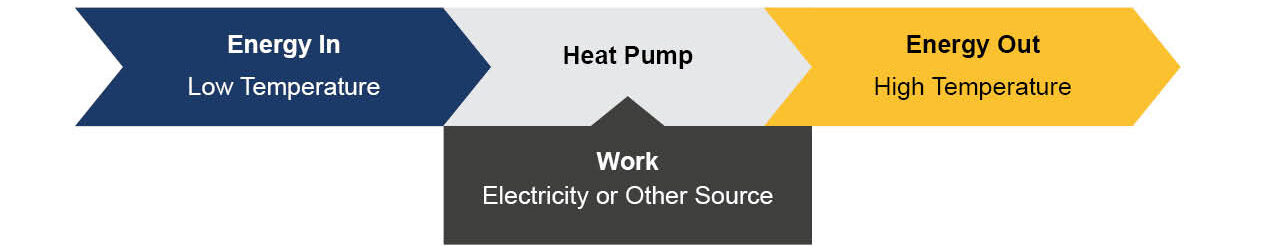

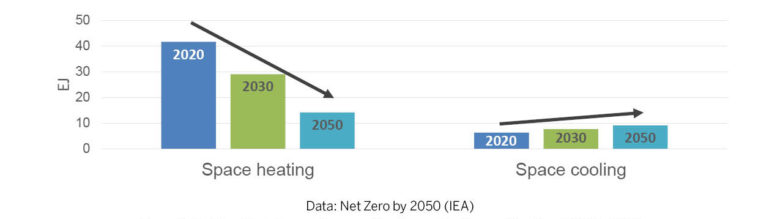

Heat pumps can meet increasing space cooling and heating demand in many regions around the world, including North America. Over the next few decades, energy consumption for space heating and cooling are expected to converge. See Figure 8. Heat pumps would emerge as a linking technology between building heating and cooling energy around the world.

Heat pumps can be deployed in urban, suburban, and rural areas with new heat pump solutions that are emerging rapidly and being deployed on a larger scale. This trend is expected to continue over the next couple of decades. Higher efficiency heat pump machines are already being utilized across the board. However, there will be specific technologies and designs that are tailored to certain buildings or climate characteristics. Air source heat pumps can be successful in low carbon buildings in most climates, while ground-source heat pumps would work better in very cold climates or in buildings that have space restrictions, such as older buildings. Selecting the right technology for the right application remains critical to the success of heat pumps in terms of cost and emissions reductions.

For more information about heat pump technology or to speak with one of our energy specialists, contact us at lowcarbon@hhangus.com or contact one of the authors of this article below.

Mike Hasaballa, M.A.Sc, P.Eng.

Mike is a lead engineer and project manager in HH Angus’ Industrial/Energy team. His work focuses on the design of efficient high-performance heating and cooling systems, as well as low carbon energy systems and energy master planning. mike.hassaballa@hhangus.com

Francisco Contreras, M.A.Sc, P.Eng., LEED, AP BD+C, BEMP

Francisco is a manager and energy analyst in HH Angus’ Knowledge Management team. He is very experienced in high performance green building design, building simulations, and energy assessment. francisco.contreras@hhangus.com